Black Influence in Architecture & Building Mastery

Tuskegee University and The Founders Who Forged the Future of Education

The intention of this article is to properly recognize a key cultural institution and the individuals who created it. In doing so, I hope to convey a long-overdue appreciation for its legacy of knowledge, competence, and practical proficiency that is unique to this historically Black University.

Tuskegee University educates and crafts leaders and professionals in a number of fields. The kind of creative professional who can plan, execute, and build in a single creative masterstroke. It’s time for people in the US and the world over to emulate this pattern so those in the fields of design, architecture, and the construction industry can once again creatively shape the world through full ownership of this design and building process.

The impact Tuskegee and its founders have had deserves both esteem and universal recognition. The key players on this stage were visionaries and far ahead of their time. Their fundamental viewpoint was that design, planning, and the full building process could be planned, owned, and executed by a single responsible professional — the Master Builder of old.

We are now seeing a sweeping return to the very standards they laid out; standards that the broader society has failed to accord proper credit where it is due. Tuskegee produced professionals who made prolific contributions to society. All the while they were forced to navigate an uphill battle in a land where they were oppressed based on the color of their skin, despite their exceptional and markedly evident competence.

Today, work for change in racial equality and justice is still an ongoing challenge we face as a nation and as human beings. Nelson Mandela wisely captured the path we need to take with his statement, “Education is the most valuable weapon you can use to change the world.” By following Mandela’s advice, we can begin to make strides towards this vital objective by giving proper recognition to the model Tuskegee set. We must also give recognition of the resounding impact on the subjects of architectural design & construction, education, and the distinguished place in history it will forever hold as a result.

First you must know the story.

Tuskegee University

You’ve heard the name, and you’ve heard the words: dedication, resolve, bravery, and strength. I have indelible recollections from my childhood. Black pilots, heroism during the Second World War, Alabama, and The Tuskegee Airmen.

These Black American soldiers overcame incredible odds in the European theatre of war, preserving freedom and democracy for the world in the midst of a segregated military. They were the first Black pilots in the US military and distinguished soldiers whose legend and legacy live on today.

The Tuskegee airman performed with trademark grace, elan, and style — then returned home to the Jim Crow laws of segregation in the United States. If you want to see them movingly portrayed, take a look at the 2012 George Lucas and Anthony Hemingway film “Red Tails” with Michael B. Jordan and Cuba Gooding Jr.

A Tuskegee graduate became the first Black 4-star general: Daniel James Jr. Tuskegee alumni shine across a broad array of fields: multi-Grammy Award winner, Lionel Richie; National Book-Award winner, Ralph Ellison; Emmy Award winner Keenan Ivory Wayans. The full list would take pages because there are many such graduates.

Yet, there is a broader scope to Tuskegee’s legacy. I have become familiar with it over the past few years through my professional life, my work, and my research for a book I am writing on the history and evolution of the architect and builder in the United States. It begins with the Tuskegee Institute.

Booker T. Washington, Robert Taylor, and the Formation of the Tuskegee Architectural Program

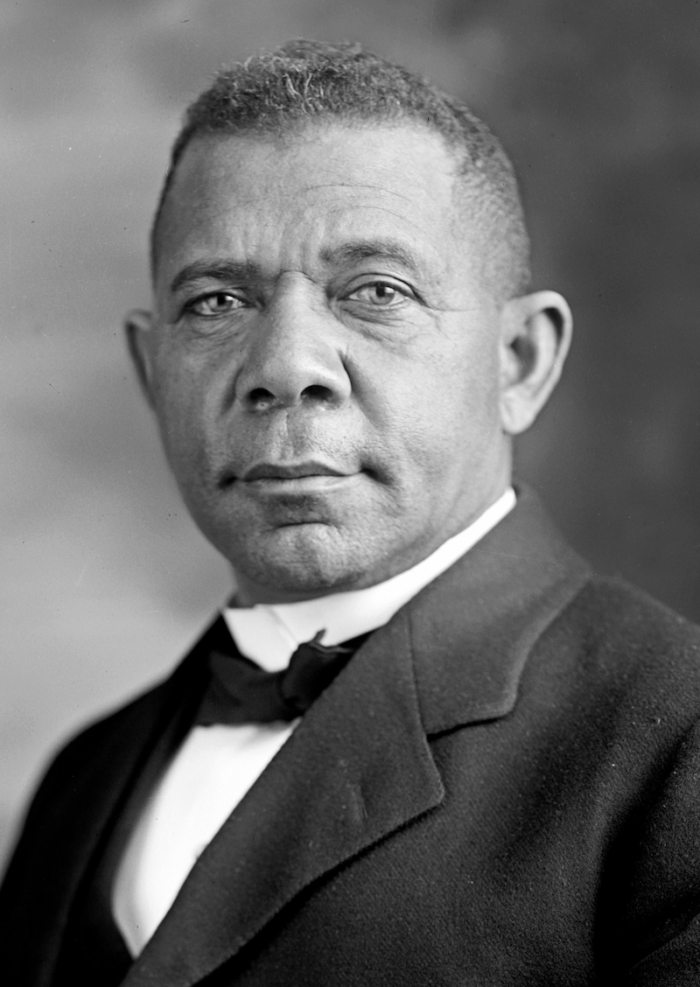

The Tuskegee Institute (now the Tuskegee University) was founded on July 4, 1881 as the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute by Booker T. Washington and Lewis Adams — both successful Black professionals who were born into slavery. (“Normal” in the historical context of the times meant it trained teachers.)

The illustrious Booker T. Washington

Tuskegee’s first and only teacher at the time was 25-year-old Booker T. Washington, an intelligent and determined Black teacher who recently graduated from Wayland Seminary (now Virginia Union University). He began teaching in a single donated room from the Butler Chapel AME Zion Church. These were truly humble beginnings.

“The cabin in which Booker Washington started his school.”

(photo credit: Johnson, Clifton, 1865-1940. www.digitalcommonwealth.org)

Following the formal abolition of slavery, the South was wrought with racism across numerous cultural strata. Mr. Washington aspired for Black men and women to be fully accepted as citizens and to gain equal footing in all walks of society. He produced students who could apply what they learned in the real world — not simply pass an examination. His mantra was “Learning to do by doing.” There were on-campus facilities for students to do just this, with a farm to raise their own food and a kiln to make bricks.

Washington recognized architecture’s power to uplift and inspire, and so from the outset sought to have buildings on campus that did exactly this. At the same time, he used the design and construction of these facilities as a practical platform for student learning.

From the very beginning, Washington always had drafting and scaled models as essential elements of the curriculums in carpentry, brick masonry, sawmilling, blacksmithing, and carriage construction. He took the architectural program to an entirely new level when in 1892 he hired Mr. Robert R. Taylor. This hiring would prove an utter game changer, and Taylor would prove a Master among Masters.

Taylor was the son of a freed slave and builder in Wilmington, North Carolina who had mastered the practical skills of building in his adolescence under his father’s guidance.

Mr. Robert R. Taylor

Taylor had been a competent builder prior to enrolling at MIT in 1888. This is significant as without this prior experience, he would not have been able to fluidly embrace Tuskegee’s hands-on, practical-based architectural program. MIT, a hallowed land of Academia, was a far cry from Tuskegee.

MIT’s architecture program was the first in an American University, spearheaded in 1866 by the newly founded American Institute of Architects (AIA), a group whose mission was to raise the social status of the white architect. Prior to this time, the word “builder” was synonymous with “architect.” A big part of the AIA’s agenda was to distance themselves from manual work, the trades, and anything else this elitist group thought would prevent them from being on par with “professionals,” such as lawyers or doctors.

The AIA’s legacy of clique-like exclusivity included barring Black membership for another 58 years after the end of the Civil War. MIT’s prestige made it the perfect institution for the AIA to implement its curriculum, steeped in theory and devoid of hands-on experience in the product of the craft. Imagine a master chef being trained to write recipes, but never learning to cook.

As this warped tradition was born (and unfortunately it still insidiously dominates the curriculums of architectural training today), Taylor flourished and managed to further his mastery for building. He was able to enhance his practical foundation as a skilled artisan with a breadth of theoretical knowledge for design. He became the first African American to graduate from MIT in 1892, and as the class valedictorian no less.

Taylor didn’t shift Washington’s focus on learning by doing, but instead elevated the standard and theory of design with his hard-earned knowledge and know-how. Shortly after beginning his tenure, the school paper stated Taylor was

“ . . . teaching the students not only how to do the work, but the principles embodied in their respective lines . . . students are not only taught how to do carpentry work, but how to draw the plans of simple buildings, estimate their costs and make out bills of lumber, and are taught to work out general problems in construction.”

The buildings the students created on campus were highly functional and aesthetically represented an elevated and improved condition for the Black professional community and American Black culture.

Unlike the AIA and the common American University, the viewpoints of these competent and professional Black men and women were not clouded by the impractical and pretentious considerations of a facade of distinction and prestige. They were interested in being effective. And so Tuskegee strode forward — setting an indelible precedence of competence and effective action.

Imagine spanning the worlds of drafting room & building site as Tuskegee students did.

(photo credit: www.fineartamerica.com)

Tuskegee and Design-Build

Tuskegee offered 25 separate degrees in the trades (such as bricklaying and carpentry), varying from 1-5 years in duration prior to graduation. All students, irrespective of trade, received a balance of theoretical and practical training, and courses on advanced mathematics and drafting were mandatory.

Training in the building trades had been in practice throughout history. To reach the pinnacle of the industry, one became an architect by progressing up through the trades. This hierarchy in training allowed for a connection and understanding by all involved, as opposed to a fractured separation and disconnect which is now the norm in our universities and the industry at large.

This trade-based approach aligned seamlessly with the Bauhaus, the school Walter Gropius would establish several decades later. Both at Tuskegee and the Bauhaus, a student could complete their studies in a shorter time span to professionally practice a specific trade. They could also continue at length to reach the position of master of construction projects (formerly known as an architect).

Today the architect is primarily only a designer — he or she can no longer necessarily actually build. The void left as leader of a project and industry at large is being filled by the Design-Builder. This is a return to the natural and holistic approach to building wherein the entire architectural creative process and course of building is executed by one solely responsible entity. There is no arbitrary fragmentation of responsibility and scope.

Washington and Taylor’s perfect harmony of theoretical knowledge and practical application resulted in a prolific 40-plus-building campus. Taylor’s comments say it all regarding the student’s practical application of their skills on University buildings:

“There is an interest, a personal touch, a devotion in the job which is to remain as a part of the school and which he (or she, as women were freely admitted) constantly sees in his work which is hard to arouse in any other way.”

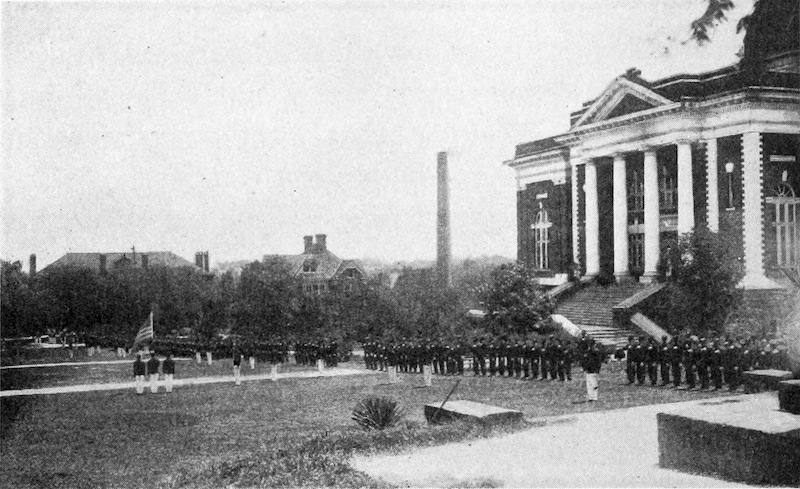

By 1915, the Tuskegee campus was the largest concentration of buildings in the US designed and built from the ground up by and for Black people.

Tuskegee was a true training ground that embodied the perfect mix of classroom and field education which is so lacking in our architectural and construction educational system today.

Photo credit: http://2018.icrps.org/campus/

Tuskegee’s Campus Today

The Tuskegee professors, students, and alumni continued to design and build. Once their campus was complete, they built churches, schools, and other structures in their community. In 1933, they became the first school to offer a construction management degree and naturally combined it with architecture to form the Robert R. Taylor School of Architecture and Construction Science (TSACS).

As inherently logical as the combination of design and construction is, most universities teaching both programs keep the classes and students completely separated. This continued the precedent for the largely disconnected and adversarial set-up we currently find our industry in.

It’s worth noting that in spite of their exceptional creations and numerous accomplishments, Tuskegee graduates were heavily discriminated against outside the borders of their self-constructed citadel of competence. When photos or descriptions of the buildings they designed and built for well-to-do white people were published in major publications, the proper credits for these outstanding works were often completely omitted. An ongoing denial of recognition of their competence, genius, creativity, and professional skill.

The Black Architect Today

Today, the Black architect is underrepresented in the USA. While 15% of the US population is Black, only 2% of all architects are. The solution to this underrepresentation of Black architects and master builders and the acknowledgment of the highly perfect educational system they created lies in recognizing the true story I am sharing here.

It’s time to end this imbalance and lift this story into prominence by giving it the respect it deserves. Robert R. Taylor’s grandniece recalled, “He was more interested in helping humanity than he was heaping up records about himself.” Let’s help humanity by shedding light on this institution and these men and women. Let us make their legacy our future.

By properly acknowledging and following the considerable legacy of Washington, Taylor, and Tuskegee, we as a nation and as a professional, creative community can enact and enable true change.

Just as the Black community has enriched America in industry, the arts, and all facets of our lives, it has also set an ideal example for the connected industries that plan, design, and build our environment and its structures.

My Humble Tribute

Currently, Design-Build education is making a comeback. In today’s world, the training of students who can do — think, plan, and execute with truly exceptional proficiency — is invaluable.

The Robert R. Taylor School of Architecture and Construction Science (TSACS) holds true to its Design-Build legacy. It has students from both degree programs working together to design and build a project that addresses a specific need of the University and/or the local community each year. The tradition lives on in over 100 architectural Design-Build programs in other US institutions of higher education. Tuskegee will forever be the first.

This movement towards truth will grow because it’s a return to the natural approach of building. In truth and simplicity there is power. In the not-too-distant future, the training of all those who dream, envision, and create the built environment — designers, construction managers, tradespersons, engineers, and so on — will be done under a coordinated hierarchy. This will necessitate both the theoretical and the practical know-how needed to construct.

This formal DesignBuild educational system has its genus in one institution: Tuskegee University.

This written piece is my humble tribute, my offering of recognition of excellence across the decades. I’d like to express and share my admiration and respect for Tuskegee’s legacy and see it properly acknowledged in both the architecture and building industry today — as well as in the current curriculum. Let us pay this proficiency forward.

And let us fight for the proper education of the industry. A return to the standards Tuskegee and its master builders established when its founders carved out professional dignity and competence in the face of bigotry and oppression. We as a culture cannot afford to have the value of these accomplishments go unrecognized or this story ignored.

Tuskegee’s educational legacy extends far beyond the bounds of architectural design and the creation of new buildings; it establishes a vital building block in the international movement towards proficiency-based education in schools. A bid to future generations that their educational processes may be thus grounded in both theory and practice. This so any student may be able to evaluate, analyze, plan and act towards the mastery of a craft — and thus the creation of a better future for humanity across all professions and fields of human endeavor.

My hope is that upon this educational path paved by Tuskegee will walk our future engineers, scientists, entrepreneurs, medical professionals, governors, true statesmen, and all who will lead. TSACS was founded on a belief in the “Power of architecture and construction science to uplift the human condition and give form to society‘s highest aspirations.”

The reward for this proper education is better buildings in which we spend over 75% of our lives and where we raise our children, grow our families, and nurture the hopes and dreams of our loved ones into the future.

With Respect & Admiration,

David

David Supple is the owner and CEO of New England Design and Construction, a Boston based residential Design-Build remodeling firm. He is currently writing books on the True History of the Architect & Builder and DesignBuild – the Natural Approach to Building. David is a graduate of Tufts University with a degree in architecture. In California, he trained as an architect for three years, designing, directing, and managing 50-100,000 square foot renovations. He founded NEDC in 2005, and rapidly established the company as a leader in Design-Build excellence, winning over 30 awards and writing in over 30 publications, with over 5 million in annual revenue and 15+ amazing team members. An aspiring comedian, he currently practices on his wife & 2 children – they don’t think he is funny.

Refs:

Book: From Craft to Profession by Mary Woods

Book: Robert R. Taylor and Tuskegee by Ellen Weiss

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Booker_T._Washington

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuskegee_University

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuskegee_Airmen

http://www.tuskegee-tacaa.org/history-of-architecture-at-tsacs.html

https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/tuskegee/btwtusk.htm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pp3_7Yo2xFw

https://www.britannica.com/event/Jim-Crow-law

https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/tuskegee/airwar.htm

https://www.tuskegee.edu/programs-courses/colleges-schools/tsacs/program-overview